Rooftop solar power has slashed Australians’ demand for electricity during the day, but left evening peak power demand largely unchanged. That’s why, as strange as it may sound, we now need to behead a duck.

With a mix of individual household, power company and government action, we could significantly reduce our demand for the most expensive peak-power that requires massive, wasteful infrastructure spending.

In doing so, we’d be tackling one of the biggest, most unfair, hidden charges built in Australians’ power bills: we could reduce the A$350 a year that households without air conditioners are being slugged to subsidise the bills of households running air conditioning at peak times.

And Australia’s 1 million-plus solar homes can play an important role in reducing that hidden air conditioning subsidy, while also defusing the argument that solar homes aren’t paying their share of electricity costs.

Solar homes powering big changes

The replacement of substantial daytime electricity consumption by PV panels on more than 1.2 million installed solar systems across Australia has visibly changed the way we draw power from the electricity grid.

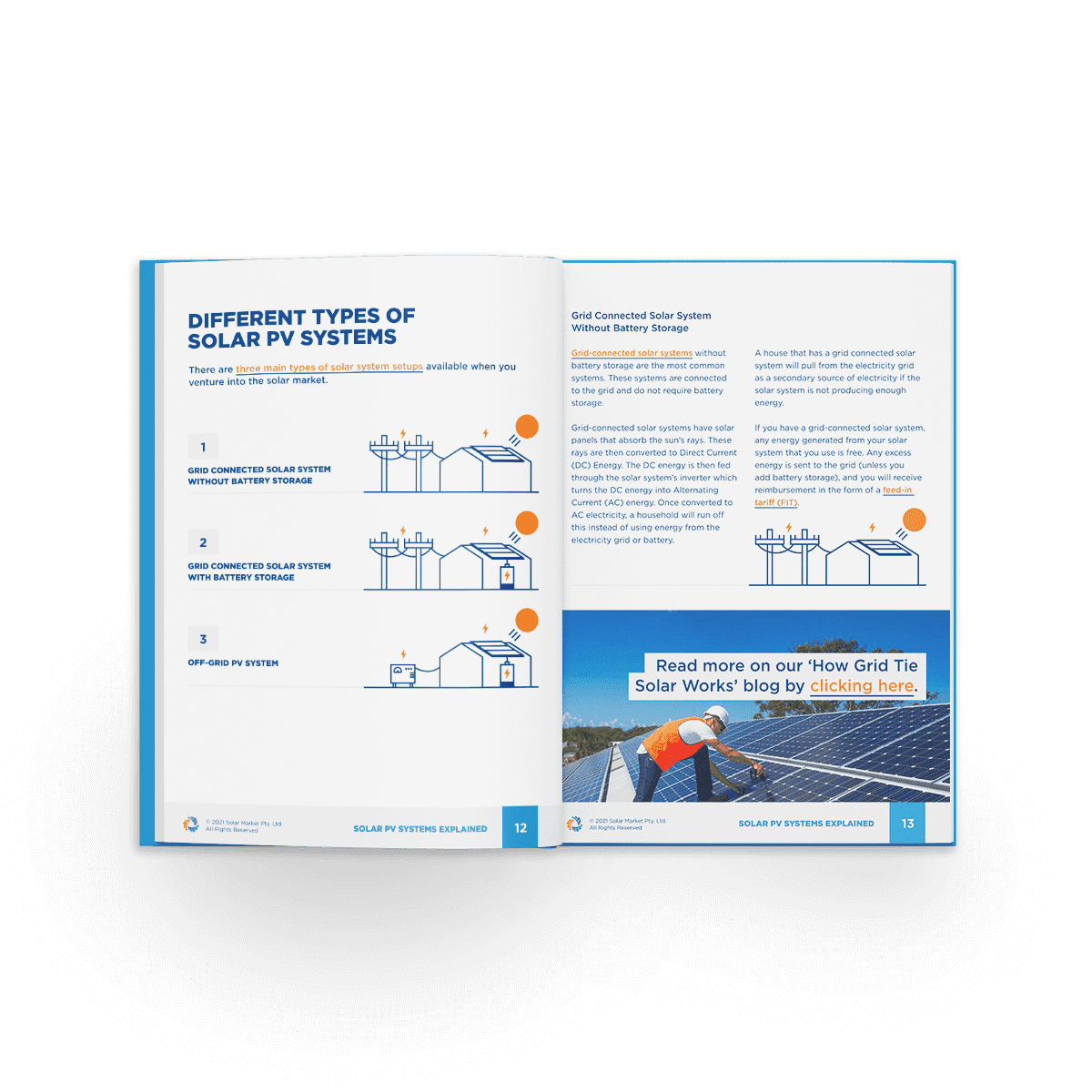

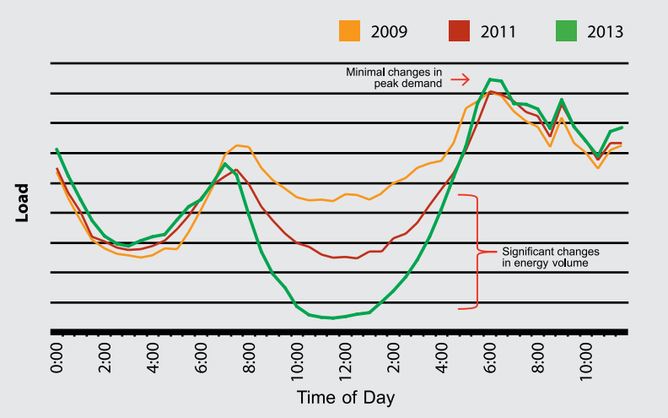

The new-look daily trend in Australians’ power use has been nicknamed “the duckâ€Â: the green line on the graph below, from a recent Energy Networks Association publication The Road to Fairer Prices, shows why!

How demand for power over the day has changed dramatically in recent years linked with the rise of solar PV panels. There is now a steep drop in demand during the day but little has changed to the evening peak, sparking this call to “behead the duckâ€Â.

Energy Networks Association, 2014, CC BY

However, Australia’s power duck is not as benign as Michael Leunig’s well-loved ducks. It drives large amounts of investment in electricity supply infrastructure – and that costs everyone connected up to a power pole more money.

So what can we do to avoid wasteful electricity spending to cut down on all our power bills?

Real solar and air conditioning costs

Many now argue that, while solar PV hits daytime electricity sales and revenue, it does little or nothing to reduce this evening peak, as shown in the Energy Networks Association (ENA) graph above. This peak now drives electricity supply infrastructure costs, which comprise around half of our electricity bills.

Indeed, the ENA – the national body representing electricity transmission and distribution businesses throughout Australia – has recently suggested that a power consumer without solar PV panels now pays about A$60 a year more to subsidise homes with solar PV panels, due to “under-recovery of network costs†during summer evening peak periods.

The rapid rise of small-scale solar PV installations across Australia.

Data from the Clean Energy Regulator, small scale installations summary data, CC BY

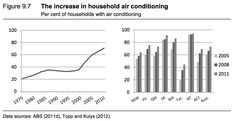

The rapid rise of home air conditioners is driving up the cost of power for all Australians. By 2020, experts warn that electricity use for air conditioning looks set to be five times greater than in 1990.

Productivity Commission 2013, Electricity Network Regulatory Frameworks, CC BY

Even so, that A$60 a year cost is much smaller than the subsidy to users of air conditioners.

The Productivity Commission estimates that the installation of each air conditioner adds A$2500 to the capital cost of powerlines and power stations: costs that all power consumers have to cover.

Much of that extra equipment is used for only a few hours each year, mainly on hot summer evenings.

However, there are ways we can reduce those big costs by cutting demand in the evening peak.

An expensive night in at home

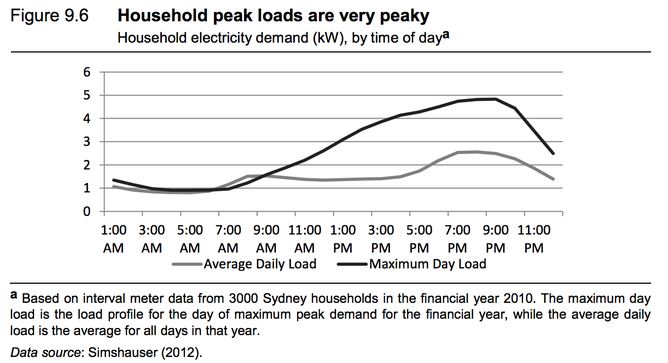

This graph below, from the Productivity Commission’s 2013 report on electricity networks, shows power use from a sample of 3000 Sydney homes. As you can see, the maximum demand for household power in the evening can be up to 5 kilowatts, or almost double the average demand on evenings for most of the year.

caption

Productivity Commission, Inquiry Report, Volume 2, Electricity Network Regulatory Frameworks, p.348, CC BY

If we look at the difference between the average and peak day, and presume that all of this peak difference is due to air conditioning load, what do we find? It seems peak demand is around 2.4 kilowatts higher between 7pm and 10pm.

It would be interesting to audit this sample of homes. Do they have large numbers of halogen lights? How many had several inefficient plasma TVs and multiple desktop computers? How energy efficient are the buildings themselves?

And what kinds of air conditioners do they have? The efficiency of your air conditioner, combined with other factors like the colour of your roof and how draughty the house is, can make a huge difference to your bills.

If most of the homes in the Sydney sample shown above have pre-2010 ducted cooling systems with poorly insulated ducts inside black tile roofs, they may be very inefficient: possibly using two to four times as much power as the best technology.

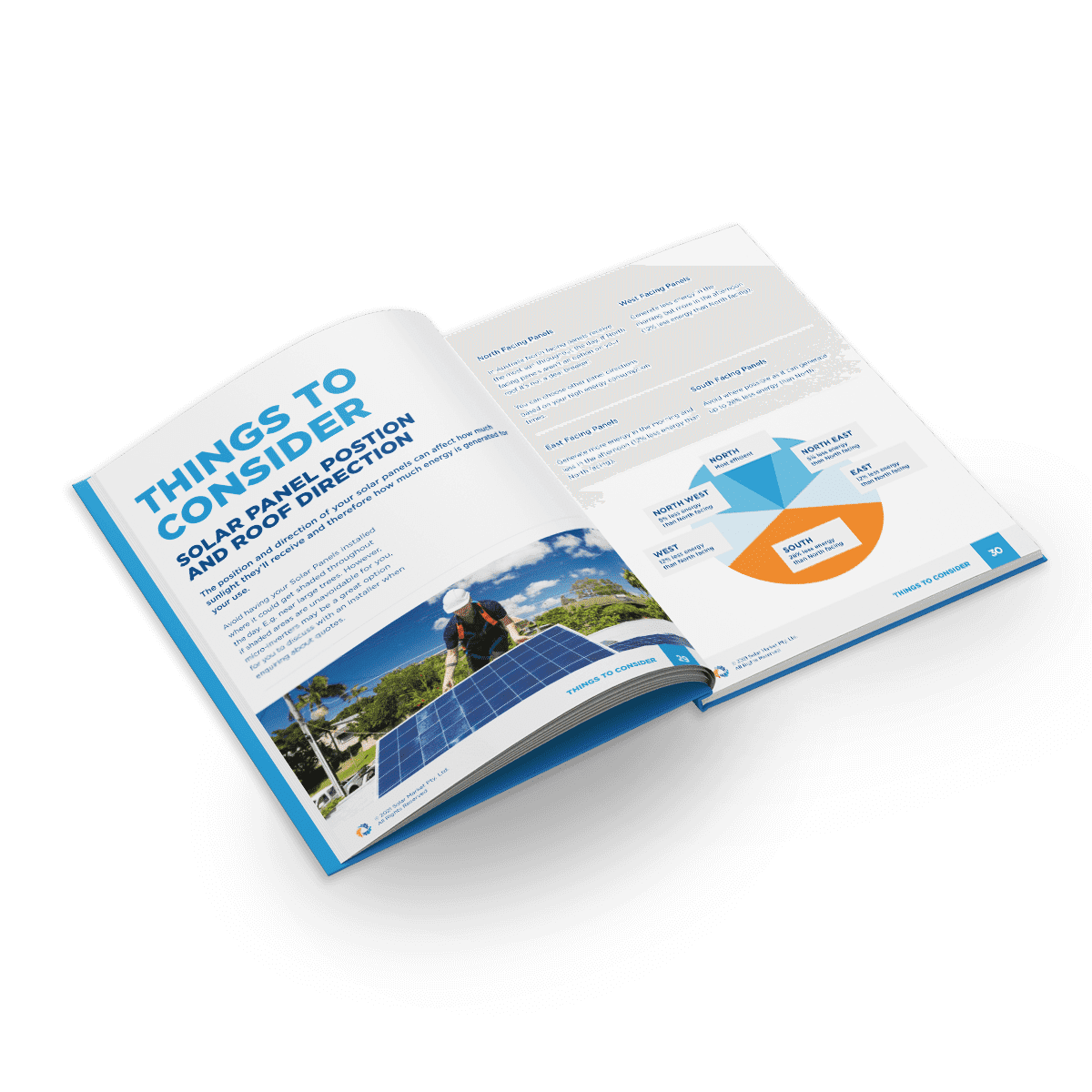

How to keep your cool without air con

One of the most common and costly mistakes people make with their electricity use is to only consider how to keep their home cool – and not to think about why it might be getting so hot in the first place.

Key factors to consider:

- Is heat from the western sun getting into the building in the late afternoon and early evening?

How much are you heating up your home without even realising it?

Denis Barbulat/Shutterstock

- Does your home have shading or heat-rejecting window films, insulation and draught proofing?

Not having those features can allow four times as much heat to enter the house as for a well-designed building – up to 20 kilowatts, equivalent to running 10 plug-in fan heaters on high setting at the hottest time of the day. And every three square metres of extra unshaded window exposed to sun adds the equivalent of another fan heater.

Hot stuff: halogen lamps.

Julio Embun/Shutterstock

- How many appliances and other heat-generating equipment are you using while trying to stay cool?

For example, running 30 halogen lamps can add 1.5 kilowatts of heat, and the radiant heat they give off can make you feel hotter, so that you turn up the air con. Two older plasma TVs can easily add another 600 watts of heat.

Cooking can add a couple of kilowatts; even more through wasteful habits such as not putting lids on pots. The range hood fan does remove some cooking heat, but also drags large amounts of hot outdoor air into the house, equivalent to a cooling load of around 2 to 3 kilowatts on a very hot day. And so on.

If we tackled those and other areas of wasteful energy use in inefficient air conditioned Australian homes, I’m confident that we could avoid at least A$250 a year in hidden subsidies for each of those houses. And we could save even more if we targeted high peak-demand homes in areas where network infrastructure is already under pressure.

But what about homeowners with solar panels: how could they help cut down on power bills?

We should be encouraging new and existing homes with solar panels to add some battery storage, as well as improving their energy efficiency in some of the ways outlined above. If we did, it would increase the amount of time when solar homes were still using their own power, also helping to cut expensive peak demand.

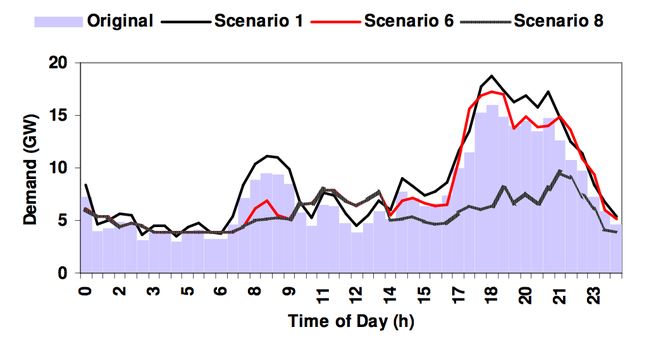

As an example of the potential for change, the graph below presents results from a UK study in which a range of energy efficiency and demand management strategies was used to cut their peak demand times.

Tackling peak evening demand with energy efficiency.

The 40 per cent House Project, Heriot Watt University, Edinburgh, 2004, CC BY

The single biggest period of demand for power in the UK happens in the late afternoon and early evening.

When the study authors added extra plasma TVs into the mix (scenario 1, the top line), power demand climbed even further. So they showed how it was possible to reduce that demand with a mix of better appliances, LED lighting and low-energy refrigeration (scenario 6, shown with the red line).

Combine low-energy appliances with more efficient LCD TVs, rather than plasma TVs, and the demand fell sharply (shown with scenario 8, the bottom line).

Cutting Australians’ cost of living

Energy efficiency is not a topic that grabs many news headlines. Yet report after report shows how under-rated it is as a way to save billions of dollars in Australia and hundreds of billions of dollars globally.

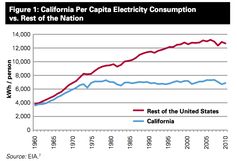

California has kept its electricity consumption relatively flat even as it’s soared across the US.

US Energy Information Administration, CC BY

But we need the electricity industry and governments to do more to help individual households, as has happened in places like California.

Significantly, if we take the steps I’ve outlined we could cut household power bills far more than by adopting a more simplistic approach of winding back Australia’s Renewable Energy Target, which is currently under review amid speculation of major changes on the way.

Instead, we could behead Australia’s most expensive duck – and end up with a tasty meal for all of us.

![]()

Alan Pears, Sustainable Energy & Climate Researcher, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.