Saving energy is a win-win. You reduce greenhouse emissions and you reduce your energy bills. However, improving energy efficiency is not an option for a significant number of people in Australia – renters.

This is important not only because rental properties account for 29.6% of Australian houses, or 2.3 million homes, but because the high proportion of low-income households in rental properties are particularly vulnerable to rising energy prices.

Those who can, and those who need to but can’t

In Victoria, only 58% of private and 55% of public rented homes have some insulation. In contrast, 95% of owner-occupied homes have insulation.

In 2009 the Victorian government found the use of electric heaters is much higher in rental properties, and that half of all rental households report difficulty heating their homes.

The relationship between low incomes and higher rates of renting is a long-term trend in Australia. More than 20% of long-term renters regularly pay more than half of their income on rent, and 17% of all private renters are on government pensions or allowances. The proportion of people with a disability, a group with higher-than-average energy needs, is also much higher in rental properties.

As energy prices continue to rise, the gap between those who can afford to improve the energy efficiency of their property and those who cannot is growing. Those who are most vulnerable to energy price increases are the people with the least capacity to improve the energy efficiency of their home.

What is getting in the way?

Internationally, split incentives (when two parties engaged in a contract have different goals and levels of information) are recognised as a key barrier to improving energy efficiency in rental properties.

The International Energy Agency estimates that, globally each year, over 3,800 petajoules of energy (roughly 65% of Australia’s total energy use in 2013-14) is not saved due to split incentives.

In Australia, several additional legislative barriers prevent improvements to rental properties.

For example, landlords can offset the entire cost of any repairs made to rental properties against their income in the same financial year. But any repair has to be like-for-like.

So if a gas hot-water system broke down in a rental property and the landlord decided to replace it with a solar hot-water heater it would be classed as an improvement, not repair. The entire cost of improvements cannot be offset in the same financial year, which deters landlords from replacing broken appliances with more efficient versions.

Many state tenancy laws require tenants to return the properties to the same condition as when they rented the property. This means even willing renters are discouraged from improving properties themselves, or engaging in energy efficiency programs offered by external parties.

The majority of leases in Australia are for six to 12 months. In Victoria you cannot get a lease longer than five years.

Therefore, tenants who do have the income and permission to improve the energy efficiency of their properties cannot be sure they will live in the property long enough to pay off the initial investment through energy savings.

Hope for change

In our 2015 study we aimed to identify solutions for the barriers to energy efficiency in rentals. We surveyed 230 tenants and landlords and interviewed five real estate agents.

We found two possible solutions that received a high degree of support from all stakeholders.

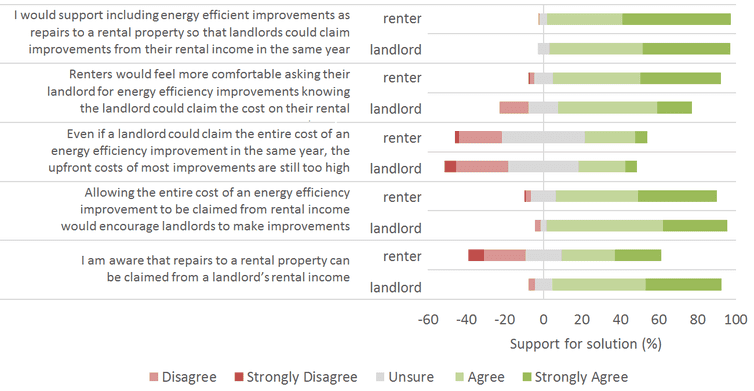

The first solution, which received over 90% support from both landlords and tenants (see image below), is to change the classification of energy efficiency improvements to repairs under tax law. This would allow landlords to offset the entire cost of the improvement in the same financial year. Real estate agents were also convinced this solution would work, with no repercussions for tenants.

Landlord and tenant responses to questions about changing the tax classification of energy efficiency improvements.

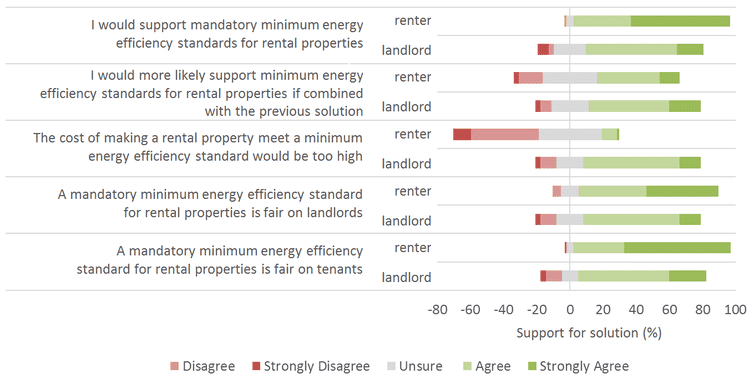

The second solution that all stakeholders supported was mandatory minimum efficiency standards for rental properties. Over 90% of tenants and 70% of landlords supported this solution (see below).

However, fewer landlords strongly disagreed with a mandatory standard if it was combined with tax offsets for energy efficiency improvements. Real estate agents agreed that the combined solution could be effective.

Landlord and tenant responses to questions about a mandatory minimum energy efficiency standard for rental properties.

Interestingly, if the mandatory minimum energy efficiency standard were enacted, it could allow landlords to claim tax offsets for energy efficiency improvements in the same financial year. This is because spending required to make a property satisfy regulatory requirements falls into the repairs classification.

The results of this study show that despite the different goals of landlords and tenants there are combinations of solutions that could overcome the barriers to improving the energy efficiency of rental properties.

If landlords and tenants can find some common ground, surely politicians across multiple levels of government can work together to find solutions for some of the most vulnerable people in our community.