Dylan McConnell, University of Melbourne

Are renewables pushing up the cost of electricity? That’s the claim made by Alan Moran in an opinion piece for the Australian Financial Review this week.

Moran, executive director of Regulation Economics and a former director at the Institute of Public Affairs, argues that increasing investment in renewables and particularly wind energy will cost consumers billions of dollars. The high operating costs and requirements for backup when the wind isn’t blowing are the problem, he argues.

But the evidence actually suggests the opposite: wind energy is already competitive with fossil fuels, will reduce electricity prices for consumers, and will play a large role in reducing Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

So, let’s go through Moran’s claims one by one.

Claim: [W]indfarms […] need three times the price at which Australian coal generators can supply electricity. Australia’s coal resources are so abundant that across the eastern states that they can profitably supply electricity at a cost of $40 a MWh. Windfarms require $120 a MWh.

It is true that black coal can supply electricity to the wholesale market at A$40 per megawatt hour (MWh). However, new wind farms require much less than A$120 per MWh to be financed. Recent experience shows that new wind farms require A$80-90 per MWh.

But this is comparing apples with oranges. The coal cost refers to what is essentially the cost of fuel. The wind cost is the cost over the lifetime of the project, including capital and return on investment.

If we compare apples with apples, the long-run cost of coal is A$85-$100 per MWh (without a carbon price), versus A$90 per MWh for wind. The short-run cost of wind is zero: flowing air costs nothing.

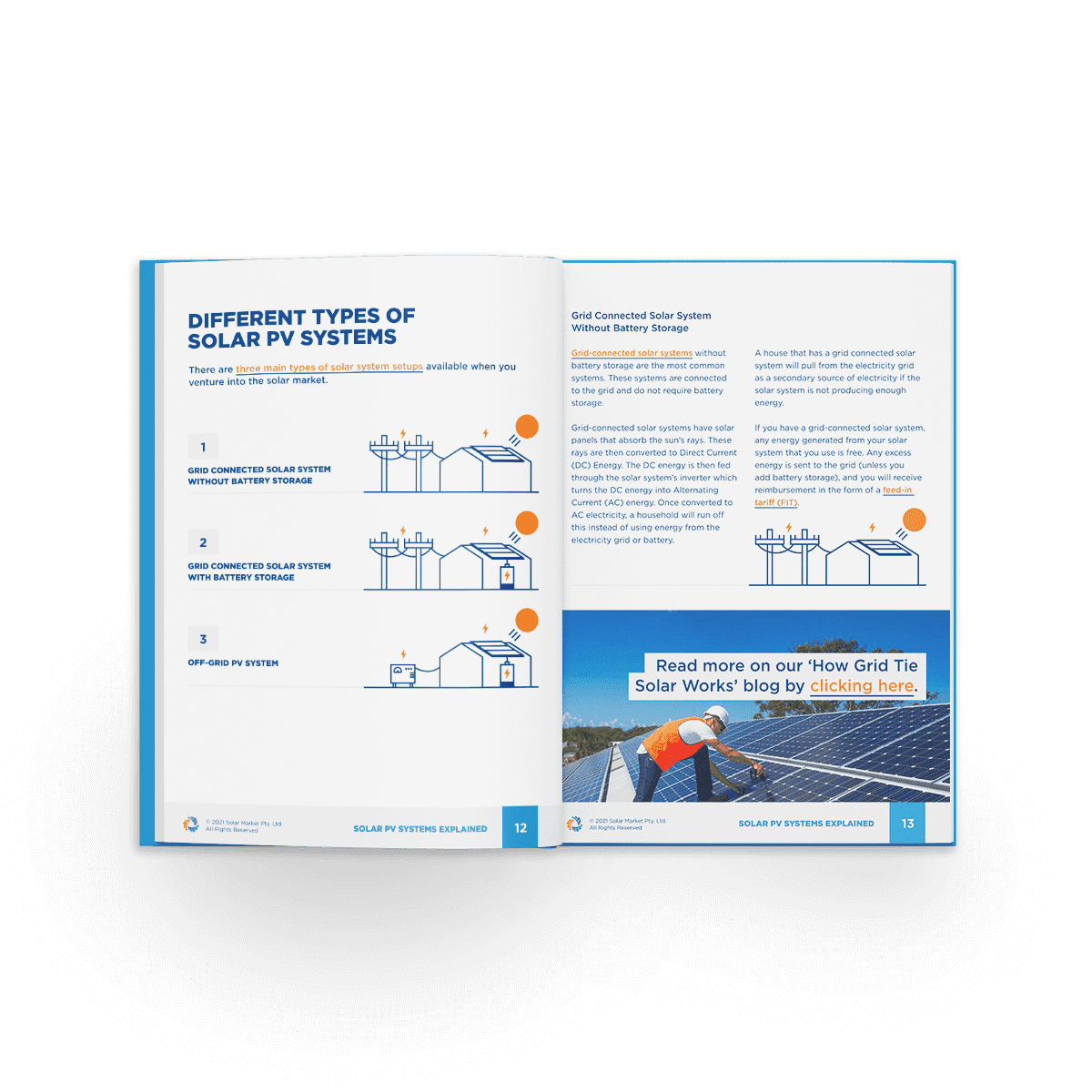

Claim: [B]ecause wind generated supply is intrinsically unreliable it needs back-up in the form of fast start generators […] Wind/solar generation in Australia currently has a 7% share of supply. That level requires 6 per cent in additional back-up, according to the estimates by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

This statement implies that additional capacity has had to be installed because of wind. This is demonstrably not true. The Australian Energy Market Operator has stated that there is no new capacity required in the next 10 years, despite the increase in wind and solar.

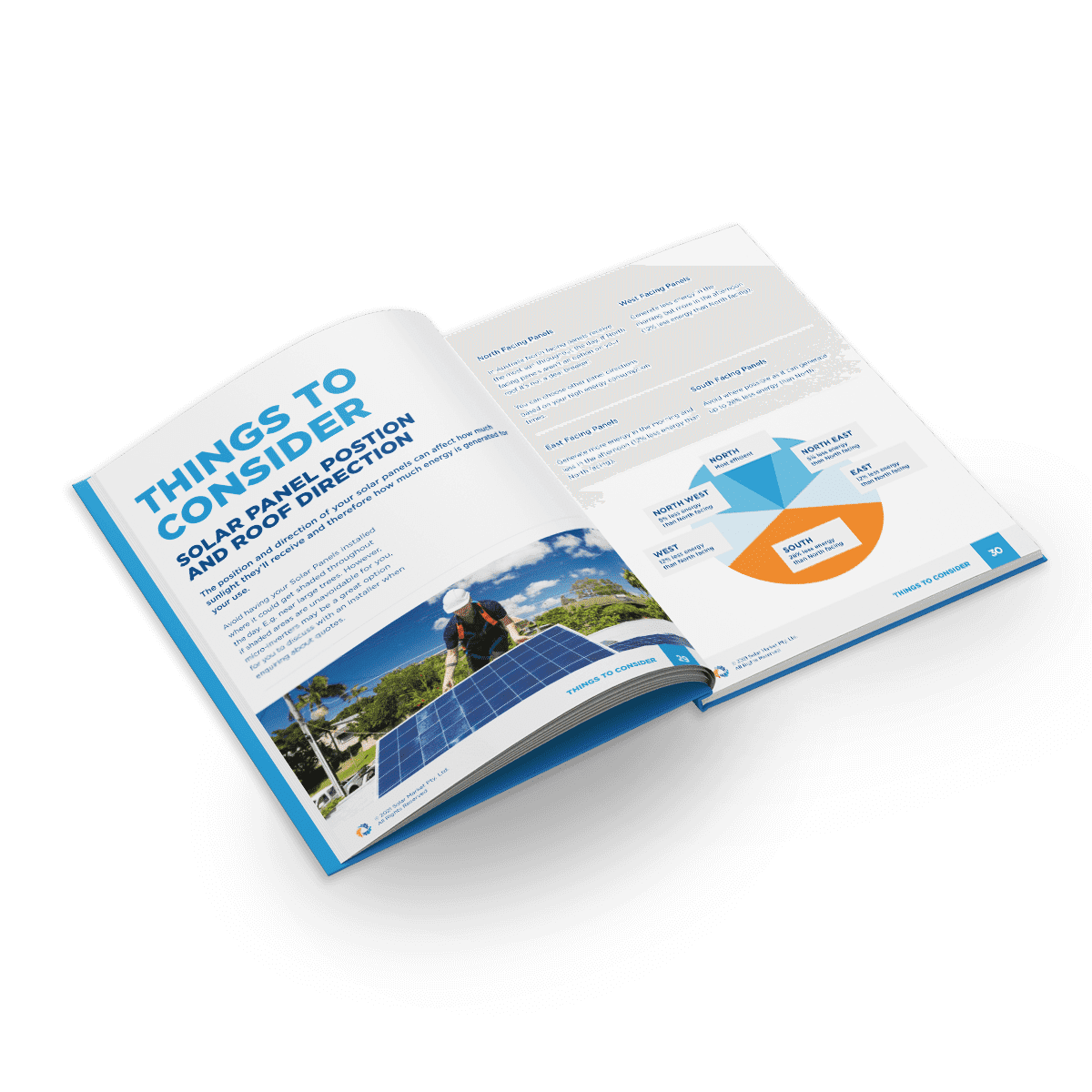

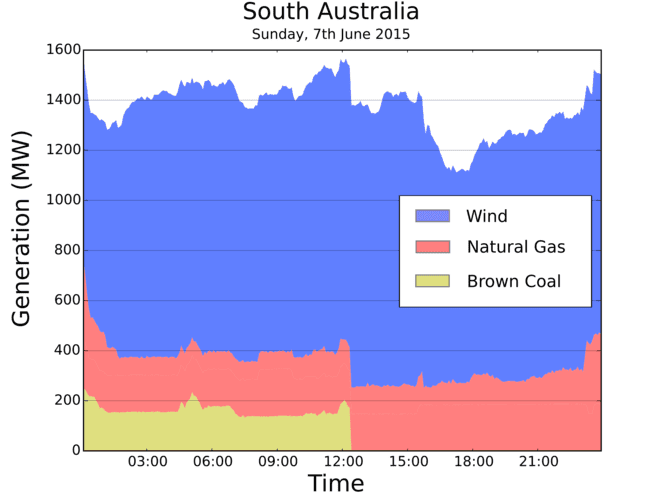

South Australia is a good example. More than 1,200 megawatts of wind power capacity has been installed, but virtually no new gas plants have been built as “backupâ€Â. In the chart below you can see that on the afternoon and evening of Sunday June 7, wind and gas met all electricity demand in South Australia.

Generation by fuel type in South Australia on Sunday the 7th of June 2015. Operations at the Northern Power Station were shut down after an explosion at around midday.

More broadly, redundant capacity is important in the entire electricity system (not just wind). All types of generation have planned and unplanned shortages.

Unplanned outages are more challenging. If a whole generator goes offline, the system must return to normal within five minutes. This is often achieved with a “fast start†generator such as a gas turbine or hydro plant. These contingency plans must equal the loss of the largest generator in the system, usually coal.

No technology is 100% reliable, as illustrated in the graph above. Wind is really quite predictable and reliable compared to coal.

Claim: Wind turbine development has been improved over the past 20 years but is now approaching its theoretical maximum efficiency. It will never be remotely price competitive with conventional generators notwithstanding wishful thinking.

As I’ve shown above, wind is already competitive with new-build coal (and gas) in Australia, and many other places around the world (including the United States). Carbon policy aside, some of the assets are seriously old and are going to be retired anyway.

A new study from UNSW Australia looked at the best energy mix for generation. Even without a carbon price, the research found that the lowest cost mix in 2050 sources only 30% of electricity from gas, with the rest supplied by renewables. About half of the gas capacity is Open Cycle Gas Turbines (for peak demand) that supply very small quantities of energy.

Claim: In aggregate terms, the annual impost on electricity consumers [of the Renewable Energy Target] is therefore from the 33,000GWh and means a cost to the customer of $3 billion a year […]

As I’ve written before on The Conversation, the government’s own modelling shows a net saving to consumers (and so does plenty of other analysis). The ACIL Allen analysis finds the target will cut power bills from 2021 onwards (by up to A$91 per year by 2030) and deliver a net saving to consumers.

Claim: Energy only comprises 25 to 30 per cent of emissions and Australia’s renewable target might therefore reduce emissions by 4 to 5 per cent.

According the Climate Change Authority’s review of the Renewable Energy Target (RET), the RET is projected to reduce Australia’s overall emissions by 58 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent.

The Government’s latest estimate of Australia’s emissions reduction task between 2015 and 2020 is 421 million tonnes. So between 2015 and 2020 alone, the RET achieves at least 13% of the reduction task.

![]()

Dylan McConnell, Research Fellow, Melbourne Energy Institute, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.